Mass Eye and Ear is celebrating its 200th anniversary, and throughout the year, the Focus blog will feature stories on the hospital’s past, present and future. This month, Focus is spotlighting the history of social work at Mass Eye and Ear, and crucial service that has helped improved the lives of patients, including those with low vision, hearing loss and laryngectomies.

In 1907, the Association for Promoting the Interests of the Blind (now known as the Massachusetts Association for the Blind and Visually Impaired) kickstarted the founding of the Social Service by funding an experimental program to discover what could be done to supplement medical treatments for the prevention of blindness. As a charitable institution, Mass Eye and Ear frequently saw patients with complex social circumstances. Many were poor and living in the city’s tenements. Crowded conditions and lack of access to education led to the spread of eye disease from tuberculosis, sexually transmitted infections and malnutrition. At the turn of the 20th century, public assistance and health programs were few and far between, and more recent immigrants struggled to take advantage of the available resources due to language barriers. Additionally, going to the hospital was often a terrifying prospect for patients, leading to delays in seeking and following through with care. It had become abundantly clear that medical treatment alone was not enough. It was time to take a new approach.

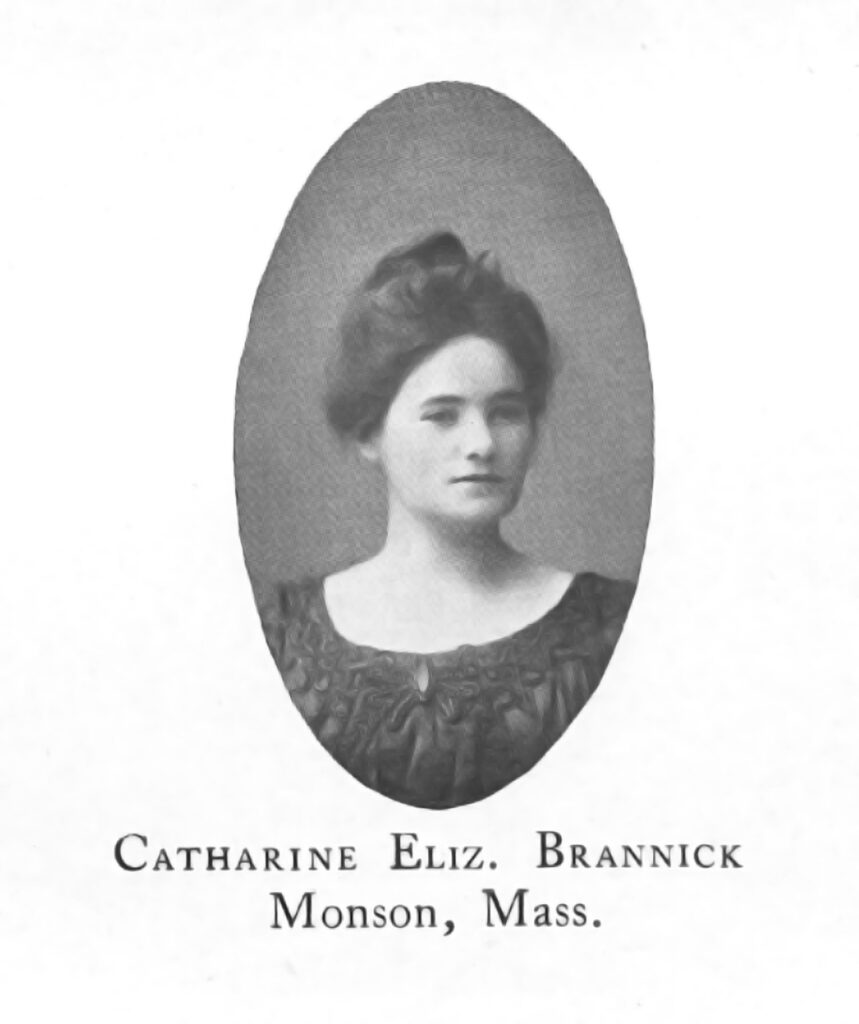

Catherine Brannick was just the social worker to take on this challenge. In her first year at Mass Eye and Ear, Brannick, a 1902 Smith College graduate and Irish immigrant, managed 325 cases and made more than 600 home visits. She provided health education for patients and families; visited homes of discharged patients and those reluctant to enter the hospital; assisted patients with finding funds for food, transportation and further care; and gave referrals to other charitable societies and institutions — all in addition to registering patients and writing case reports. As the service developed and expanded, Brannick also led a push to advocate for better public health services for people with visual and hearing disabilities. Despite her busy schedule, she never lost sight of the importance of connecting with patients and earning their trust through compassion and empathy. Although she would only lead the fledgling department for four years, her determination and spirit of care left a permanent mark on what social work at Mass Eye and Ear would become over the following decades.

By the 1940s, many of the challenges of Catherine Brannick’s day had at least somewhat dissipated. There had been a marked increase in public health and welfare services resulting from the Great Depression, and the introduction of antibiotics in 1928 and progressive improvements in anesthesia and surgical techniques meant that doctors could perform increasingly complex procedures with greater success. Needs were changing, and so too did the focus of the Social Service.

In the 1940s and 1950s, advances in neonatal care meant premature babies were more likely to survive than ever before, but doctors started to notice that a worrying number of them were going blind shortly after birth. This condition, first described by Mass Eye and Ear’s Dr. Theodore L. Terry in 1941, was retrolental fibroplasia, today known as retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). Scientists would later learn that ROP was often caused by babies receiving too much oxygen after birth, the result of the oxygenated incubators that had become more readily available in developed countries.

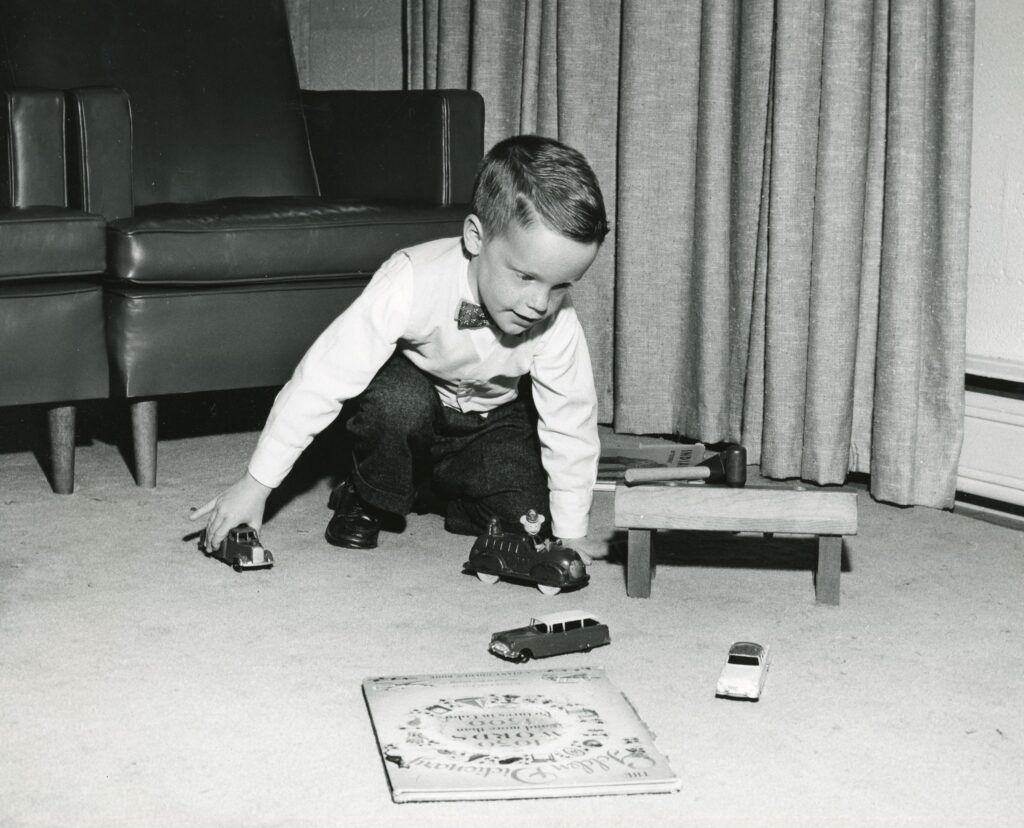

While doctors and researchers worked toward finding causes and effective treatments for ROP, the Social Service was developing strategies to set these children up to live full and successful lives outside of the hospital. Social workers believed in the importance of empowering families to care for their children in the home during the pre-school years, rather than sending them to institutions, as was common at the time. The Social Service hired a nursery school teacher, Pauline Moor, to work with parents in the home (she would also establish a joint Summer Institute for children with ROP at Perkins School for the Blind). Her program was so successful that it became a model for others throughout the state. Social workers also found themselves using evolving ideas about psychology to teach parents how to effectively process their emotions as they navigated the challenges of raising blind children in the face of social stigma and limited access to community resources.

The 1940s also saw the creation of the Winthrop Foundation for the Deaf at Mass Eye and Ear. Under the leadership of Dr. Ruth Guilder and in close collaboration with the Social Service, the organization’s founding mission was to improve the language skills of deaf children. Through the Winthrop Foundation, children were able to access hearing aids at an early age, as well as participate in a first-of-its-kind teaching program before they entered primary school. Dr. Guilder was an early proponent of the idea that deaf children could thrive in schools alongside hearing children, and the Social Service worked to evaluate individual patients for placement in “mainstream” programs. Once in school, social workers coordinated the students’ schooling plans, and they also held educational meetings for school personnel to better understand the needs of students with hearing disabilities. Just as with children with ROP, social workers’ advocacy for deaf children meant many of them could stay in their homes and benefit from closeness to their families and loved ones.

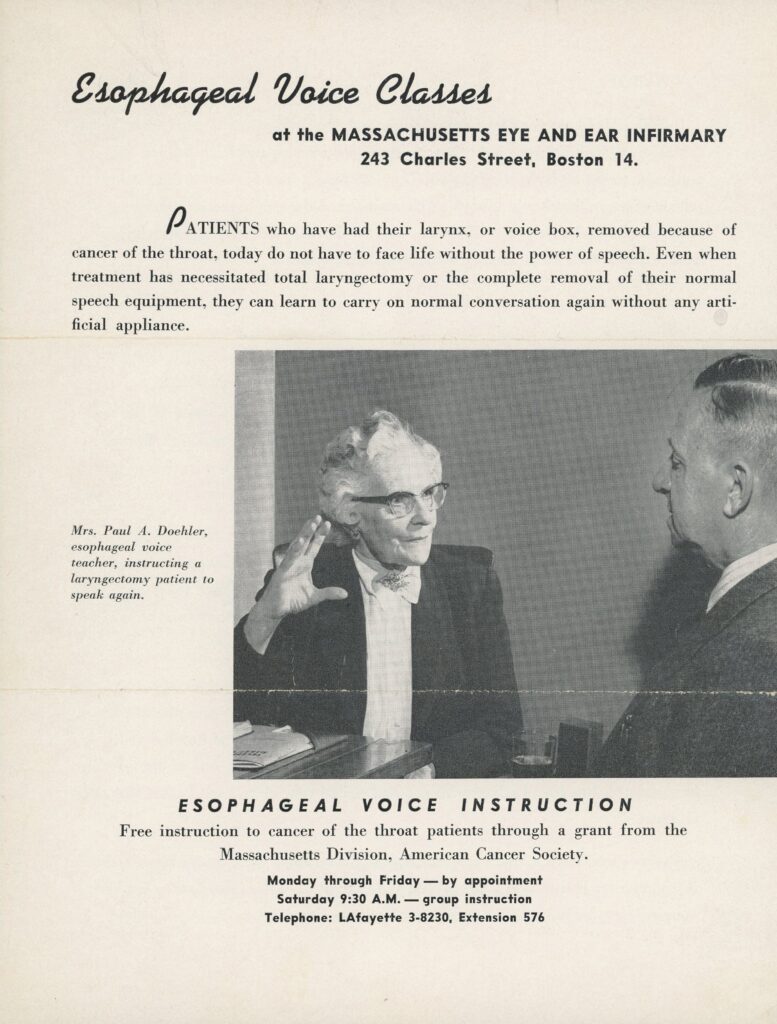

For patients who undergo laryngectomies, or the removal of the voice box, adjusting to the loss of their natural voice is a major part of the recovery process. After losing her vocal cords to cancer in 1944, Mary Doehler taught herself to speak again using her own self-taught technique for esophageal speech. A teacher before her laryngectomy, it was only natural that she wanted to share her knowledge with others. She coached patients in esophageal voice for free at Mass Eye and Ear, ultimately helping to restore the speech of at least 1300 patients. She was also instrumental in teaching the technique to patients and voice therapists around the world, recording her manual for teachers in her own voice as a testament to its power. Today, Mass Eye and Ear’s social workers continue to provide laryngectomy patients with counseling, education and hope.

Mass Eye and Ear was also at the forefront of developing rehabilitation services for patients with low vision, a category of vision impairment that cannot be corrected with traditional eyeglasses, surgeries or medications. Since the founding of the hospital’s Low Vision Clinic and Vision Rehabilitation departments, social workers have been partners in assessing individual patient needs to connect them with the resources they need to live independently. This can include teaching patients to use specialized assistive devices to do everyday tasks like reading, as well as helping them with access to transportation, housing, and food.

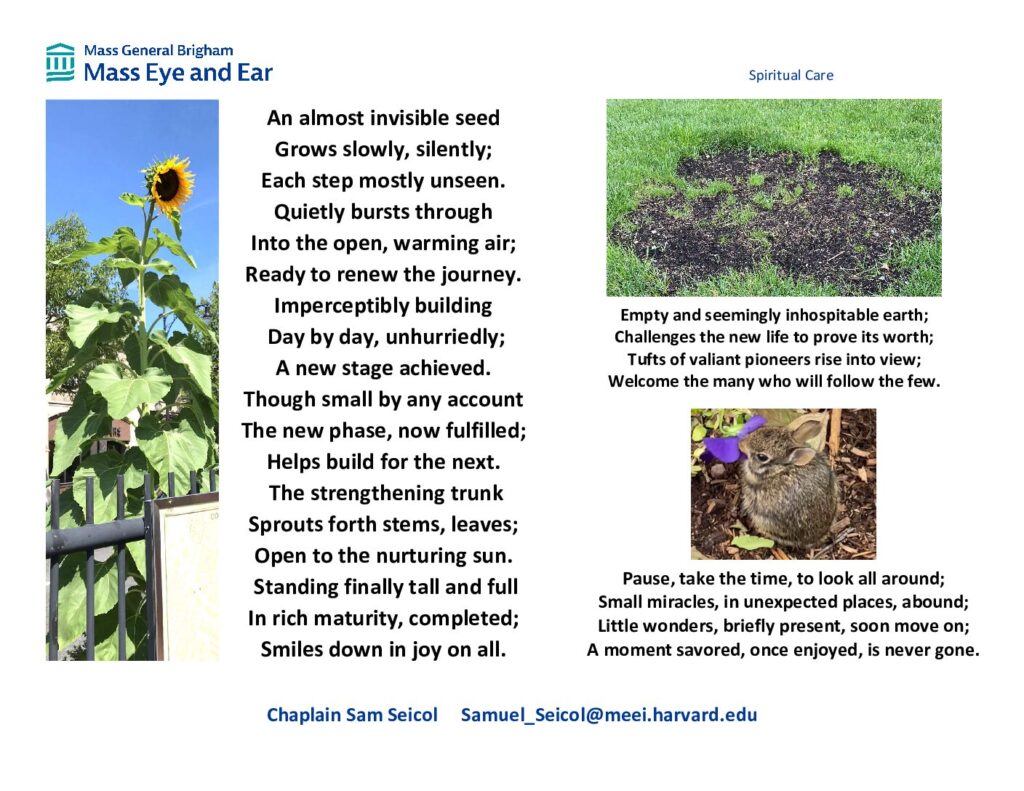

Social work as a practice has evolved tremendously since the early 1900s, both as a discipline and as a part of the Mass Eye and Ear care team. The department continues to look ahead, developing new programs and initiatives for the wellbeing of our patients. Around 2014, Social Work brought Chaplain Sam Seicol to MEE to provide support to those in need of someone to talk to or confide in, to process grief in the wake of change and loss, or to provide blessings, prayers, or meditations. While Seicol makes frequent rounds in the hospital’s inpatient units, he also works closely with Social Work, Nursing and most recently, Music Therapy, to identify patients who may benefit from spiritual care and create treatment plans that meet them where they are, regardless of culture or belief. Among Spiritual Care’s most popular initiatives are Seicol’s photography and poetry, which he creates weekly for staff relaxation and reflection and offers to patients and families as Reflection Cards, along with nature music videos created in collaboration with Music Therapy. Both resources are available on the Spiritual Care homepage.

Launched by the Social Work department in 2021, Mass Eye and Ear’s Music Therapy program uses music to support patients’ physical, emotional, cognitive and social needs. Music Therapist Peri Strongwater, MA, MT-BC, and her team work with each patient’s medical providers to develop individualized treatment plans tailored to their diagnosis, needs, personality, culture or interests. As Peri told Focus, examples of Music Therapy in action include using music to reduce pain and anxiety before and after surgery, using singing with outpatients with voice disorders to cope with voice loss or changes, and using music listening to support ear training for recipients of cochlear implants. Through music, patients can tap into their creativity and joy, and feel more empowered in their care.

Though the healthcare landscape has changed in many ways, social workers continue the pioneering work of their predecessors who broke new ground to raise awareness and understanding about the complex emotional, psychological and socioeconomic effects of illness on patients and families and the benefits of compassionate care.

The advent of Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid and most recently the introduction of the Affordable Care Act have created more complex public and private healthcare networks for patients to navigate. Social Workers at Mass Eye and Ear advocate for patients and families and help them connect with various programs and resources in the community to maintain access to care and improve quality of life.

Special thank you to Mary Gregory, MA, MLIS, for her contributions to the section on Catherine Brannick.