Mass Eye and Ear doctors recall how the bombing impacted their careers.

Aaron Remenschneider, MD, MPH, was the senior resident on-call at the Mass Eye and Ear Emergency Department on April 15, 2013. In this role, the fourth-year otolaryngology—head and neck surgery resident was on point for triaging ear, nose and throat (ENT)-related emergencies at Mass Eye and Ear and neighboring Massachusetts General Hospital that afternoon and evening. Little could Dr. Remenschneider or anyone anticipate, a tragic and cataclysmic event would occur that would forever change the lives of many and alter the career paths of clinicians and researchers at Mass Eye and Ear.

Just after 2:45 PM, two bombs exploded within seconds of each other near the finish line of the Boston Marathon on Boylston Street where crowds were gathered. The blasts injured hundreds of individuals and took the lives of three people. Hospitals in the area, including Mass Eye and Ear, immediately mobilized to help, with Dr. Remenschneider being among the first to field calls on incoming patients.

“It was immediately apparent that there were many people who had ear-related injuries,” Dr. Remenschneider recalled to Focus ahead of the tenth anniversary of the bombing. “We took care of dozens of patients that day at the Mass Eye and Ear and Mass General emergency rooms.”

In addition to treating patients in the immediate aftermath of the bombing, many of whom had ruptured eardrums, more than 100 patients would come into Mass Eye and Ear in the days and weeks that followed, reporting symptoms like hearing loss and tinnitus, a persistent ringing in the ears.

Looking back, Dr. Remenschneider said the experience showed that there was much unknown about how to optimally treat patients amid such an unprecedented scenario.

“We didn’t have a lot of information about how to care for a mass civilian-related blast injury, most of the research available on blast injury had been performed in the military,” said Dr. Remenschneider. “There was a consensus and a very open feeling amongst otolaryngologists and other specialists across Boston hospitals, that we should put all of our data together in order to learn from this event.”

Research efforts spurred that remain today

Dr. Remenschneider, who entered his final year of his otolaryngology residency in 2013, worked closely with two attending physicians at Mass Eye and Ear who were seeing these patients, otologists Alicia Quesnel, MD, and Daniel J. Lee, MD, FACS. Together, they enrolled patients who sustained injuries in the bombing to track their ear and hearing-related outcomes. They ended up following more than 100 patients for several years.

In a study published one year after the bombing, the team reported ear related injury was the most common injury sustained. In addition, 90 percent of hospitalized patients sustained a tear or rupture in their eardrum, and the standard surgery to repair them – called a tympanoplasty – was successful 86 percent of the time.

“The success rate of the procedure was not as high as in the general population,” said Dr. Remenschneider. “We believe the blast wave likely had a negative impact on the eardrum’s ability to heal. This experience for me and others highlighted the need to improve our techniques and materials for eardrum repair.”

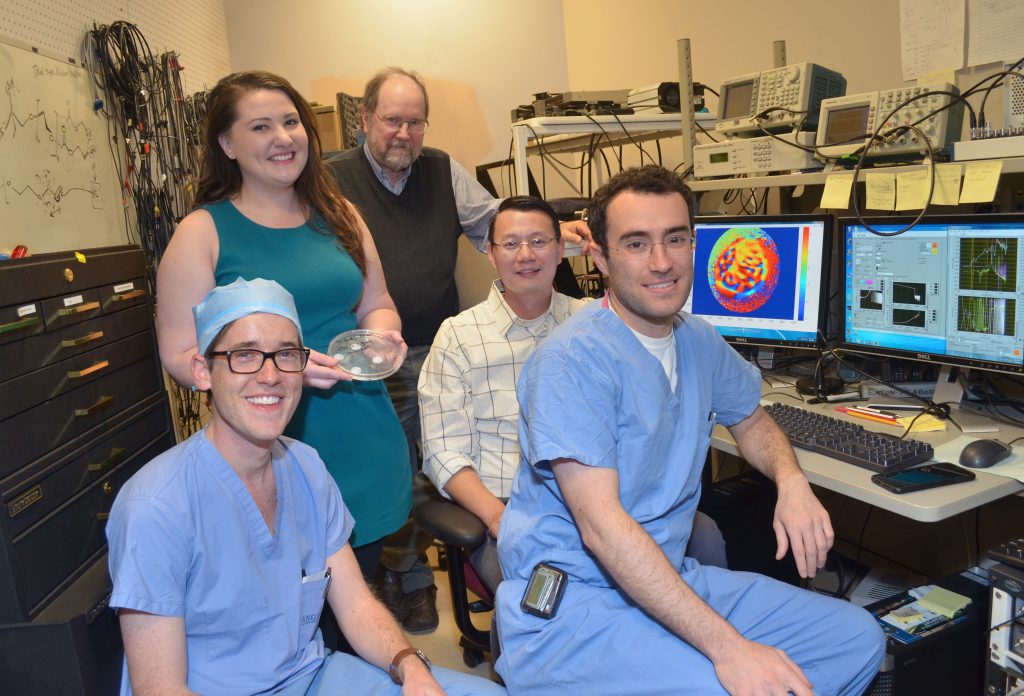

That led Dr. Remenschneider and colleagues to look towards improved methods and newer materials to optimize the outcomes of patients who require a tympanoplasty. Over the following six years, Dr. Remenschneider and colleague Elliott Kozin, MD helped lead a team of researchers at Mass Eye and Ear, Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, and Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, to develop a 3D-printed eardrum repair solution called the Phonograft. Rather than relying on traditional methods to repair a ruptured eardrum with skin or cartilage harvested from elsewhere in the patient’s body, the Phonograft uses 3D printing to manufacture biomaterial-based grafts that can serve as an acoustically tuned construct to improve healing and hearing outcomes after eardrum repair. A company, co-led by one of the inventors, Nicole Black PhD, who worked as a PhD student and a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard and Mass Eye and Ear, is currently working to bring the Phonograft to clinical trials.

“The research and clinical experience from working with patients after the Boston Marathon bombing played a critical role in my motivation to develop 3D-printed graft materials,” he said. “This event has significantly influenced my research path.”

Tinnitus research inspired by tragedy

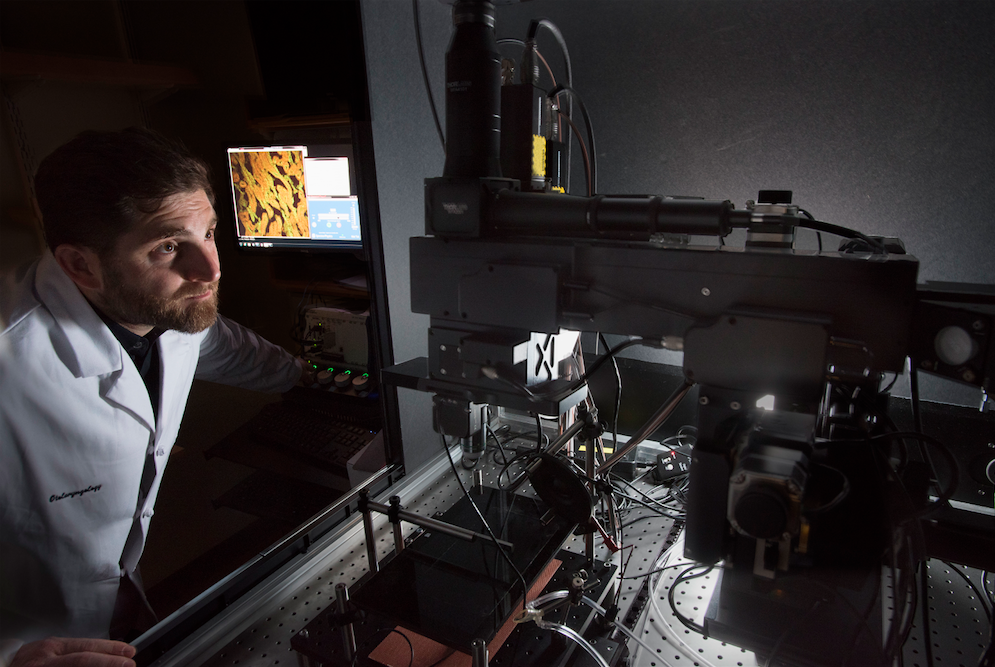

Hearing scientist Daniel Polley, PhD, has dedicated his research career to finding better ways to diagnose and treat forms of hearing damage missed by the audiogram, the gold-standard hearing test. In his role as director of the Lauer Tinnitus Research Center, he and his colleagues conduct studies in a quest to develop new diagnostic and treatment strategies for tinnitus, or ringing of the ears, which affects more than 50 million people in the U.S. alone. Tinnitus has no cure and is lacking in effective treatment solutions for patients.

Dr. Polley said he remembers the exact day he became interested in tinnitus as a research question: April 15, 2013. Hundreds of people who never had tinnitus the day before suddenly had it following the bombing due to their proximity to the blast.

The charitable organization set up to aid victims of the bombing, called One Fund Boston, fielded many complaints of tinnitus in the months that followed. That led the organization to put out a call to local medical centers to try and find a way to help these individuals. Dr. Polley was one of the researchers who stepped up to try.

“What we learned from this experience wasn’t so much how to get rid of tinnitus, but what we would need in order to find an effective therapy,” said Dr. Polley.

The experience led Dr. Polley and his colleagues to look for a biomarker for tinnitus. A biomarker is a measurable biological marker of a disease or disorder. Just as a biomarker of a tumor is needed to better diagnose cancers and provide targeted treatments, one would be needed for tinnitus, he explained. Even today, tinnitus cannot be measured on an audiogram, and instead, a patient receives a questionnaire when they present with a complaint of ringing in their ears.

“Since the marathon bombing, we’ve invested years of research into finding an objective biomarker for tinnitus,” said Dr. Polley, who along with colleagues closely studied the ear and brain in their search for one. “Nothing stuck until fairly recently.”

After screening many patients with tinnitus in the lab, the team began to see a pattern that these individuals showed subtle and involuntary changes in their skin conductance, pupil dilation, and facial reactions – a function of their autonomic nervous system activating. This nervous system response reflects the body’s unconscious fight or flight mechanism; however in people with tinnitus, the response is more activated.

“The work is still ongoing, but these new measures seem to provide a signature for the psychological burden of tinnitus,” said Dr. Polley.

Armed with a promising biomarker, this work has led to testing interventions aimed at modifying this response. One promising area is in the form of digital therapeutic software. Dr. Polley has led studies, including with marathon bombing victims, in which participants are trained on software that gets their brains more acclimated to hearing in noisy environments. The results show they can better tune out the tinnitus and pick up more words than prior to training on the software. He points out that much work remains to improve these digital therapies and get the effects to last longer. But in a field where treatments are so limited, it’s been a positive and meaningful step forward.

“We’re on the cusp of a new era of treating hearing disorders,” said Dr. Polley, who added that gene therapies and other approaches are also in development. “We may one day be able to provide a meaningful reduction for people with tinnitus and an improvement in hearing.”

Reflecting on eye injury care after the bombing

Retina specialist David M. Wu, MD, PhD, had recently joined Mass Eye and Ear in 2013 and was seeing patients at the recently opened Longwood campus, when he noticed a crowd around the TV in the waiting room. With a packed clinic schedule and the day winding to a close, he went back to seeing a patient when an alert came in asking all clinicians in the area to stand by and prepare for injuries and casualties.

“That was the first indication that something significant had happened,” he recalled.

Across Boston at Mass Eye and Ear’s main campus, Peter Veldman, MD, was rounding on a trauma patient who had undergone surgery the previous day and happened to have the TV on. In real time, he saw the news coverage unfold.

“I remember thinking, this is going to be a very big deal, and Mass Eye and Ear is going to play a central role in the response,” he recalled to Focus. Once he finished with his patient, Dr. Veldman was contacted by chief of ophthalmology, Joan Miller, MD, and tapped to lead the eye emergency care response across the Harvard Ophthalmology network. Dr. Veldman was the Ophthalmology Chief Resident at the time, and in that role, was also director of the Ocular Trauma Service. That emergency plan would entail coverage for not only Mass Eye and Ear’s ED, but for other hospitals with affiliated residents and faculty, including Mass General, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Some marathon spectators who had acute injuries, such as shrapnel or foreign bodies in and on their eyes, walked into Mass Eye and Ear’s ED for care. Throughout Boston, ophthalmology residents and attending physicians stationed themselves at trauma centers in order to assist with any eye injury concerns. Many patients presenting to these hospitals with an eye injury had other serious injuries, most commonly to their lower limbs, and doctors often provided consultations in the emergency department, in surgeries for other injuries and in the intensive care units.

One particular case stood out to Dr. Veldman. He operated on a patient who experienced a significant eye injury from a BB pellet used in the pressure cooker bomb. That patient also had extensive leg and foot injuries, so careful coordination was required in between the doctors of different specialties to ensure the best possible management of both leg and eye injuries.

“This was a day where one could get easily overwhelmed by the cruelty of the bombing. As I look back, it clearly is also a day when Boston’s world-class health care networks were able to come together to provide a tremendous response,” said Dr. Veldman.

Dr. Wu was called upon to treat a patient at Brigham and Women’s Hospital who was admitted for surgical care of severe lower extremity injuries. This patient had also suffered significant retinal damage. Given its severity, the treatment would require the tools and imaging of an ophthalmology-specific operating room at Mass Eye and Ear.

“Repair of complex retinal detachments requires specialized equipment and a staff that handles these types of surgeries daily,” said Dr. Wu.

The patient had sclopetaria, in which the shockwave from the blast caused a rupture within the eye without an object directly penetrating the eye’s globe. What was rare was that this patient also experienced a retinal detachment, which was thought to be uncommon with these ruptures.

“This eye was in very terrible shape,” said Dr. Wu. “At the same time, the patient was also undergoing life-saving treatment for non-ocular injuries. But everyone was so motivated and came together to make this work.”

The patient was transported via ambulance to Mass Eye and Ear, a practice that required the care and coordination and delicacy that the surgery itself would also require. There, a surgical team led by Dr. Wu and Dean Eliott, MD (now director emeritus of the Retina Division), performed a successful retinal detachment repair. The patient was then transferred back to the Brigham to allow continued rehabilitation from their other injuries.

“It took a lot of people to make that one surgery happen,” said Dr. Wu.

Another patient operated on at Mass Eye and Ear experienced a similar injury, which would lead to a series of published case studies that described how to treat these uncommon injuries.

Drs. Veldman and Wu, along with their colleagues in the Mass Eye and Ear Ophthalmology Department also detailed their experience in a medical journal article published a year after the bombing, which offered guidance on best practices in the event of future tragedies.

“The tragedy brought to the fore the importance of having protocols in place,” said Dr. Veldman, who is now an associate professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Science at The University of Chicago Medicine. “We were fortunate that Mass Eye and Ear was and remains one of the highest-volume eye trauma centers in the world. While the circumstances of this tragedy were uniquely frightening and difficult, the injuries themselves are what Mass Eye and Ear clinicians manage routinely.”

In the decade since, trauma has played an important role in Dr. Veldman’s career. He’s given lectures around the country as a visiting professor and, along with a number of other former chief residents including Drs Ankoor Shah, Alice Lorch and Matthew Gardiner, taught a trauma course for the American Academy of Ophthalmology for three years.

For Dr. Wu, the experience also had a lasting impact.

“The experience taught me that in times of crisis, the medical community will do whatever it takes to come together,” said Dr. Wu. “The marathon is such an institution in Boston and this tragedy struck a lot of people’s hearts. I’ll never forget that level of collaboration between Boston hospitals.”