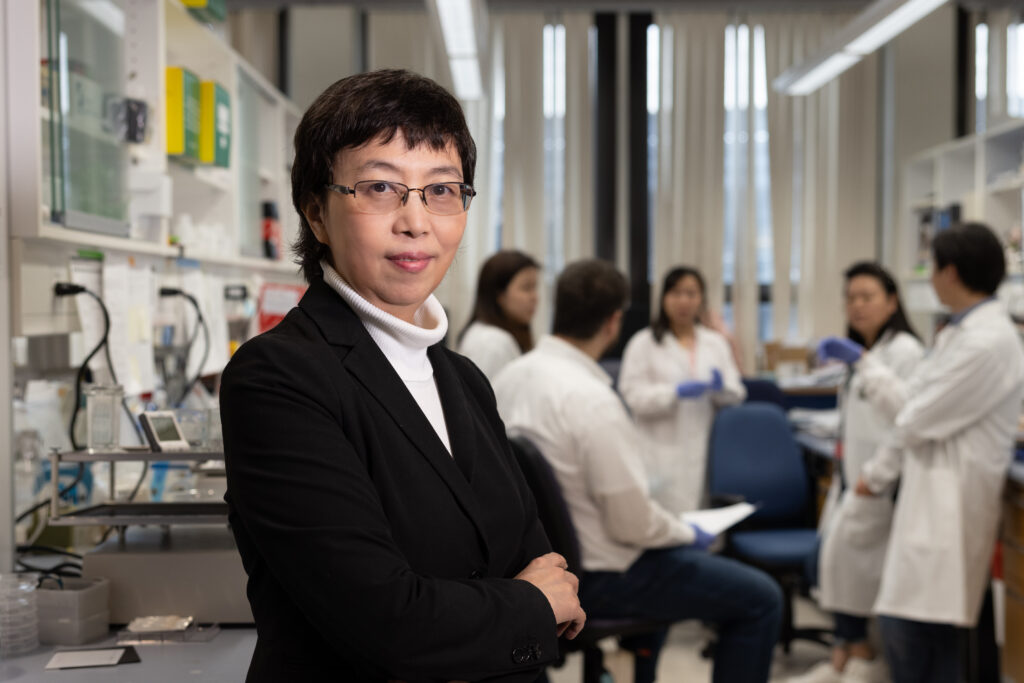

Mass Eye and Ear scientist Dong Feng Chen, MD, PhD, uncovered the role of a protein, IGFBPL1, which shows a promising pathway to stall vision loss in glaucoma.

How glaucoma causes blindness has long been a mystery and now, a groundbreaking discovery from Mass Eye and Ear scientist Dong Feng Chen, MD, PhD, may shed new light on this mechanism and lead to a promising treatment strategy. Dr. Chen’s work has uncovered a link between neuroinflammation, immune cells in the eye, and the damage that causes blindness. Neuroinflammation is the immune response mounted in areas of the body with delicate brain cells including the brain, spinal cord and light-sensing cells and neurons in the eye’s retina.

Her research team uncovered a switch that could turn off this inflammation, stopping damage to these neurons and reversing the mechanism that leads to blindness in glaucoma. Interestingly, this mechanism may be involved in Alzheimer’s disease and other neuroinflammatory disorders. The team published their research August 29 in Cell Reports.

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases that lead to blindness. More than 3 million people in the United States and 80 million globally will receive the crushing diagnosis. “Glaucoma is a devastating, blinding condition,” said Dr. Chen. “It’s actually the most frequently diagnosed neurodegenerative disease.”

Eye drops or laser surgery can manage glaucoma when detected early, but both merely slow down the progression and don’t halt the disease. As glaucoma progresses, it damages the ganglion cells, which process information sent from the eye to the brain via bundles of nerve fibers. The retinal ganglion cells responsible for vision die off, leading to irreversible vision loss.

“Our paper proves there is a common mechanism causing neural degeneration in the eye and the brain,” said Dr. Chen. “We have now discovered a way to stop the neuroinflammation.”

Dr. Chen’s research and FireCyte, a company she co-founded with support from Mass General Brigham (MGB) Innovation, seek to find ways to prevent the blindness caused by glaucoma. Additionally, they hope what they’ve learned about neuroinflammation in the eye could inform treatment or prevention of other neurodegenerative and inflammatory disorders.

“The eye is a perfect model for studying brain problems,” said Dr. Chen. “It’s easily accessible and a simplified model that makes structural and functional losses much easier to assess.”

Understanding how glaucoma damages the eyes

Glaucoma is often associated with high pressure inside the eyeball — called elevated intraocular pressure. But the pressure itself isn’t what damages the eye’s structures, said Dr. Chen.

Previous work by Dr. Chen and others has highlighted the role of the inflammatory immune response in glaucoma. Their research has found that a triggering event — typically high intraocular pressure but sometimes other factors — can cause an immune response and inflammation.

“When you bring the intraocular pressure back to normal, the immune response continues to hurt the neurons in the eyes,” said Dr. Chen. “This is why fixing the pressure does not solve the problem of glaucoma.”

Immune cells called microglia that live in the eyes and brain drive this immune response. “Microglia are like police — actively surveying the environment to detect and eliminate potential threats caused by infections or injuries in the eyes,” explained Dr. Chen. “When infections or injuries occur, the microglia become activated to defend the neurons.”

When they need to mount a defense, the microglia recruit immune cells called T cells. Typically, the brain and retina are ‘immune privileged,’ meaning no T or B cells circulate there. But when the microglia get activated, they call in these immune cells. Studies have found microglia play a critical role in neurodegeneration in the retina with glaucoma and in the brain with other diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

In the case of glaucoma, microglia and T cells cause inflammation, damaging the eye’s neurons and retinal ganglion cells responsible for vision.

“We guessed that when this injury happens, and the microglia are activated, there has to be a way to stop that process,” said Dr. Chen. “These T cells must be called back and told, ‘Your job is done; be quiet and be nice – don’t hurt your own cells.'”

“We hypothesized that there must be a way to do that, but nobody knew what it was,” said Dr. Chen.

The role of IGFBPL1 in neuroinflammation

In their new study, Dr. Chen’s team focused on determining what mechanisms may be involved in regulating these pathways. They screened for molecules that correlate with retinal ganglion cell survival and found a protein that acted like a switch that the retinal cells use to call back activated microglia, thereby stopping inflammation and damage to the eye.

The molecule is called IGFBPL1 and is little known. “It was surprising — we looked up this new molecule on PubMed and found only maybe ten papers,” said Dr. Chen. “Nobody knew what it did.”

The researchers performed several experiments to understand the roles of IGFBPL1 and microglia in models of neuroinflammation of the eye and glaucoma. When they gave normal microglia IGFBPL1, there was little response. But giving this protein to activated microglia returned them to a normal resting state.

“This was something nobody had ever seen before,” said Dr. Chen. “It told us that IGFBPL1 is acting like a switch to turn off the inflammatory response.”

The team made a mouse model that lacked IGFBPL1 and found with this mechanism gone, the microglia become and stay activated. This activation led to neurodegeneration and development of glaucoma and Alzheimer’s disease-like features.

They then tested the protein in a mouse model of glaucoma with high intraocular pressure and signs of neuroinflammation and vision loss.

“We found this stunning effect of rescuing normal visual function — not only supporting the survival of the retinal ganglion cells but also stopping the entire inflammatory process,” said Dr. Chen.” We almost cure the disease; we stop the neurodegeneration.”

Turning discoveries into treatments

Understanding this pathway and finding IGFBPL1 is the first step in stopping blindness caused by glaucoma. The researchers are now working to turn these discoveries into treatments.

“That’s why we started the company, which is funded by the MGB Innovation,” said Dr. Chen. “We’re leveraging this protein to generate a drug to treat glaucoma.”

This company, FireCyte, is partly funded by MGB Ventures. Dr. Chen and Bill Yelle, a former Entrepreneur in Residence at MGB Ventures and now CEO of FireCyte, co-founded the company. They are developing novel treatment strategies for progressive neurodegenerative diseases in the eye and exploring different methods of targeting this pathway. They hope these innovations not only can help unlock the mysteries of neuroinflammation in the eye, but other diseases.

“As a scientist, I came into this venture knowing little about the drug development process,” said Dr. Chen. “The MGB Innovation team coached me on how to think about drug development and convert our preclinical research into potential human therapies.”

Very interested in learning more and seeing the potential benefits for many patients.

I have severe glaucoma. Please keep me updated on your progress as I would be interested in joining any trials your company may conduct

My husband has been suffering with Macular Edema since 2019 from cataract surgery we are still searching for any help he may be able to receive to assist with his diminishing eyesight. We are in Pennsylvania and have traveled to Merci Eye in 2021 ,but left almost hopeless. If it’s at all possible, I can take the trip again if it may help him. His name is Glenn A Black.

Thank you