A new device brings relief to restless kids with Down syndrome and sleep apnea

About four years ago, Brendan Whalen’s mother, Diane, of Newton, Mass., noticed some changes in her son. He didn’t seem well rested, and was often a bit grouchy — something that was out of character for the then-12-year-old, who also has Down syndrome. A sleep study at the doctor’s office offered an explanation. Brendan had severe obstructive sleep apnea, or shallow, disordered breathing that would startle him awake at night.

The family tried just about everything to help Brendan, now 16, sleep through the night. Doctors removed his tonsils and adenoids. Brendan slept with a tennis ball tucked into the back of his shirt to prevent him from sleeping on his back. He had a palate expander put in. A CPAP machine helped for a while, but Brendan often woke up in the middle of the night to pull the mask off his face.

“No matter what we tried, he was still waking up all the time,” Diane said. “He was exhausted.”

The signs of exhaustion reached into just about every corner of Brendan’s life — socially, academically and physically.

“Doctors warned us that not sleeping could do a lot of damage to his health,” Diane said. “We didn’t want him to shorten his lifespan because he wasn’t sleeping.”

In July, Brendan had life-changing surgery with Dr. Christopher Hartnick, Director of Pediatric Otolaryngology at Mass. Eye and Ear. A new device, the hypoglossal nerve stimulator implant, has helped Brendan’s body find the rest he so badly needed.

Down Syndrome and Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Patients with Down syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea have long needed better solutions for their condition. Key characteristics of their anatomy, such as larger tongues that fall back in the mouth during REM cycles, can obstruct the airway during sleep, and a sensitivity to the feeling of a mask blowing air onto the face makes the traditional therapy for obstructive sleep apnea, a CPAP machine, a nightmare for these patients.

Without any favorable options to turn to, and with the threat of cardiovascular issues like high blood pressure and heart disease if the sleep apnea is left untreated, physicians and patients’ families are sometimes left with the difficult decision to resort to life-altering tracheostomies, if the obstruction is severe to the point of not being safe.

Stimulating a Nerve in the Neck to Open Up the Airway

In 2015, Dr. Hartnick began a clinical trial studying the use of the hypoglossal nerve stimulator in these patients. Relatively new technology, the device had recently gained momentum as an alternative to CPAP therapy.

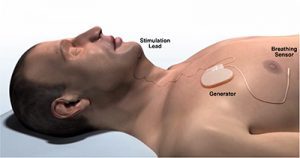

By stimulating a branch of nerves in the upper airway, the hypoglossal nerve stimulator causes the tongue to move forward and out of the airway during sleep. In surgery, doctors place a cuff around select branches of the nerve, tunneling a wire down to a receiver in the chest, and another to a sensor below the ribs. The sensor detects breathing and sends up a signal to the stimulator cuff, which sets the whole process into motion.

Last month, the research team published some new results. One year out, the first six children in the trial have seen anywhere from 56 to 85 percent reduction in the severity of their sleep apnea symptoms. All were safely implanted without any complications. Perhaps most exciting, for Dr. Hartnick, is that the children are using the machine to help them sleep for long stretches of time without turning the device off.

“They’re using the machine up to 60 hours per week,” Dr. Hartnick said. “The kids don’t even feel that it’s on, so the success rate of keeping the machine on has turned out well.”

Living with the Device for Better Sleep

Patients can program the technology to turn on at a certain time each night, approximately half an hour after they fall asleep.

“Brendan is able to control this himself, which is a real confidence booster for him,” Diane said. “He also won’t go anywhere without it.”

But perhaps most importantly, Brendan is himself again. He’s able to focus more in school, and he’s participating in a way that he wasn’t able to a year ago. His teachers report that he raises his hand in class more often.

A Saturday morning sports program no longer brings him to exhaustion, and family walks on Cape Cod are no longer extremely brief.

“At the beginning of the summer, Brendan would stop and sit down in the sand after about 15 minutes of walking on the beach, because he was too tired,” Diane said. “Over Thanksgiving, we walked on the beach for an hour and a half. He was able to keep up and was happy to do it. He wasn’t tired.”

The clinical trial has now expanded to more centers throughout the country. For more information, please reach out to Jennifer_Sessa@meei.harvard.edu.