New research findings offer explanation for why this eye disease is found in central cornea and far more common in women

A discovery by Mass. Eye and Ear researchers provides new clues that may help better prevent and treat a genetic eye disease that causes vision loss called Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy (FECD).

The researchers, led by Dr. Ula Jurkunas, have identified a possible mechanism that may explain why the condition only affects certain parts of the eye and is much more common in women. Specifically, they found that exposure to ultraviolet A (UVA) light sets off an enzyme reaction that causes the DNA damage seen in patients with FECD. This reaction was much more pronounced in females, as it is driven by the activation of CYP1B1, an enzyme that converts estrogen into metabolites that cause DNA damage. The researchers were able to replicate this damage in mouse models and human cornea cell tissue.

The findings were published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

FECD is a complex disorder that has multiple genetic factors that cause the disease to manifest in a similar way despite the different backgrounds, explained Dr. Jurkunas, who led the study and performs corneal and refractive surgery at Mass. Eye and Ear. That drove her team to look for mechanisms and environmental changes that happened on a cellular level, regardless of genetics, she said.

“This research finally offers an explanation for clinical observations that ophthalmologists have long seen in patients with this complex disorder,” Dr. Jurkunas told Focus. “It is so crucially important to identify modifiable risk factors for genetic diseases like FECD, as it enables clinicians to tell our patients that there might be ways to reduce risk for the disease regardless of genetics.”

Disease first presents as blurry vision that won’t go away

FECD is a progressive vision disorder that typically starts for people in their 50s and 60s, when they begin to experience symptoms that often include blurry vision in the mornings, significant glare from headlights and other light sources, and visual disturbances that can last throughout the whole day. Ophthalmologists diagnose this condition following a comprehensive eye exam including a slit lamp test, and use non-invasive imaging called specular microscopy to measure corneal thickness and swelling.

Some studies have estimated 1 to 4 percent of the U.S. population may have FECD, and research has shown the disease is far more common in women. FECD is a leading cause of corneal transplantation worldwide, with an estimated 75 percent of these transplant cases occurring in women.

Partial thickness corneal transplant, also known as descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK), is the most common surgical treatment, in addition to experimental therapies such as descemet stripping without endothelial keratoplasty (DWEK). Much research over the past decade has looked closely at genetic factors that cause FECD, but until now, a study has not reported on an underlying mechanism that may represent a modifiable risk factor.

Observations in clinic spur study

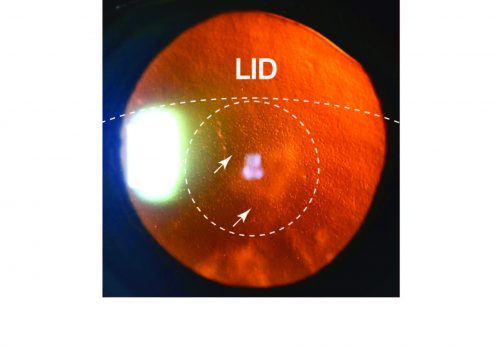

Mass. Eye and Ear has one of the highest-volume treatment programs of FECD in the United States. Dr. Jurkunas, who is referred patients from all over the country, noticed that hundreds of her patients with FECD had similar signs and symptoms. For example, FECD caused scarring that always occurred in the center of the back layer of the central cornea, while the periphery was often clear and unaffected by disease. Since the center of the cornea is what in the eye gets exposed to light, her team theorized that UV light exposure may play a role in the disease.

They put this to the test by exposing the central cornea in adult mice to UVA light, where they were able to induce formation of FECD. This was confirmed through years of additional testing.

Next, the researchers came across a more unexpected finding, that female mice were more likely to have more severe and earlier onset of FECD compared to males. Knowing from clinical observation and previous research that women were more affected than men by FECD and more likely to get surgery, Dr. Jurkunas and her team wanted to see if the UVA light somehow played a role in the sex differences.

They tested this theory by exposing a human corneal endothelial cell culture to UVA light. The researchers then discovered a novel pathway where the UVA light causes increased expression of an enzyme called CYP1B1, that jump starts an estrogen metabolite pathway that ultimately causes DNA damage. This increased estrogen formation correlated with the sex-dependent differences in disease presentation, they reported.

“That is the mechanism that explains what we have been seeing in our patients,” said Dr. Jurkunas. “We tell our patients with cataracts and macular degeneration to avoid exposure to UVA light, and our study suggests we should start telling our Fuchs’ patients as well,” said Dr. Jurkunas.

Future research to look at interaction between genes and light exposure

FECD has been a long-standing basic science research focus for Dr. Jurkunas and her colleagues for more than a decade. In 2010, Dr. Jurkunas’ lab was the first to extensively demonstrate that there’s a link between oxidative stress and Fuchs’ dystrophy. In 2o16, Dr. Jurkunas and her team identified a link between mitochondrial dysfunction in corneal endothelial cells and the development of FECD.

Future studies from her group will look at the interplay between genetic and environmental factors to address why certain people, notably women, are more likely to develop FECD than others. Many people get significant exposure to UV light but not everyone develops disease. More epidemiological studies are needed to better determine this risk, but for now, people with genetic risk factors for FECD may want to wear protective eye wear and limit unnecessary light exposure.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/ National Eye Institute grants R01EY020581 (UVJ), Alcon Young Investigator Grant (UVJ), core grant P30EY003790, Research to Prevent Blindness Award (UVJ); Alcon Research Institute Young Investigator Award (UVJ), New England Corneal Transplant Research Fund (UVJ), Japan Eye Bank Association Overseas Grant (Miyajima T), Bausch and Lomb, Ocular Surface Research fellowship (Miyai T), Japan Eye Bank Association Overseas grant, (Miyai T), Nakayama Foundation International exchange grant (Miyai T), American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (18POST34030385) (VK), and Shire Research Scholarship (SOT).

In addition to Dr. Jurkunas, study authors include: Cailing Liu, Taiga Miyajima, Geetha Melangath, Takashi Miyai, Shivakumar Vasanth, Neha Deshpande, Varun Kumar, Stephan OngTone, Shan Zhu, Dijana Vojnovic, Yuming Chen, and Eleanor G. Rogan, Muhammad Zahid.

I am an 84 year old patient of Dr.Jurkonas who has Fuchs. When I was a teenager I was treated with Ulta violet light (heat lamp) and xray directed at my face for acne. I have had multipal cancerous moles on my face. And now, maybe Fuchs? I live in Albany,NY.

I am 53, have been working for almost 30 years using dental curing lights. As per the light manufacturing companies the lights were relatively safe to look at for a few seconds at a time, I am wondering if it accelerated my Fuchs since the worst damage was to the eye that was in the direction of the light cure unit and got the most exposed over time. To correct this I have had two transplants done over the past year.

Given the use of light cure technology that has expanded into nail salons etc, and the number of female operators, I was wondering if there should not be more warnings given.

Hi Dr. Doron, thanks for reading and your comment and sorry to hear what you’ve gone through with this issue. More study is planned on this topic to determine the risk and links to Fuchs, which may ultimately lead to some new guidance and warnings for patients. We’ll be sure to update our blog as more information becomes available.