Mass Eye and Ear is celebrating its 200th anniversary, and the Focus blog each month will have stories on the hospital’s past, present and future. In May, Focus is spotlighting Mass Eye and Ear’s Nursing Department and its dedicated professionals who pioneered the care of patients needing services in our specialty hospital.

In advocating for the nursing profession and to recognize the contributions of nurses, the International Council of Nurses and The American Nurses Association designate a week each year centered on the birth of Florence Nightingale (May 12, 1820). This month, Mass Eye and Ear joins them and commends the nurses who have transformed care for patients over the past 200 years since the hospital’s founding. Although advances in technologies have evolved, patient care has been at the forefront of the nursing mission at Mass Eye and Ear for the past two centuries.

Early days

In the earliest days when the hospital operated out of one room, there wasn’t a great need for nursing care. But as it grew from that small clinic founded in 1824 to a fully-fledged hospital over the next decade, so too did the need for a core group of qualified nurses to support care. Because of the specialized nature of the hospital, it was thought its nurses should also have specialized training.

Up until the 19th century, most care of the sick was done in the home by family members. With increasing urbanization and industrialization, hospitals began to flourish to care for those who had no means of caring for themselves. The rise of hospitals led to the need for trained nurses to staff them. Similar to today, nurses worked alongside doctors to nurture patient recovery. They dispensed medications and dressed wounds. They also ensured sanitary standards were met, following the practices promoted by Florence Nightingale. In 1872, the first nursing school in the U.S. was established at the New England Hospital for Women and Children, and in 1873 the Boston Training School for Nurses opened at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). By 1890 there were 30 nursing schools in the country, graduating 470 nurses a year. As nursing schools proliferated, so too did nursing specialization, evolving with the profession.

In 1895 Medical Superintendent Farrar Cobb, MD, embarked on a mission to professionalize nursing at Mass Eye and Ear. He was among a group of doctors and administrators who understood that nursing, and in particular specialized nursing, was pivotal to the success of a modern hospital. One of his first acts as superintendent was to hire Miss CEM Somerville, RN, a graduate of Boston City Hospital School of Nursing, to lead the service as Matron and Superintendent of Nurses. Prior to Somerville’s arrival, matrons had received no formal medical training.

The Postgraduate School for Nurses

Cobb and Somerville established a four-month postgraduate program in aural and ophthalmic nursing. Entering nurses were expected to have graduated from a hospital school. The curriculum was rigorous, consisting of training in the wards and outpatient departments, instruction in sterilization and dressing, and lectures and classes led by visiting surgeons, house officers and the superintendent of nurses. The lectures had titles such as “Pathology of the Eye and Ear,” “The Nurse as Social Worker,” “Medical and Surgical Nursing to the Special Senses,” and “The Eye in Art and History.” Upon completion, nurses were encouraged to apply for a position at the Hospital. The first year, there were 65 applicants to the postgraduate program. Thirty-two were accepted, 26 received diplomas and six failed.

Mass Eye and Ear also established a program for “attendant nurses,” or what would be considered nursing assistants today. This group was made up of women of “good character” who had no previous qualifications but were interested in hospital work. They were trained in the basics of patient care and after one year were encouraged to start formal coursework. The goal was to create a competent workforce, not just for the general good but to provide for the unique needs of a specialty hospital.

The Coonahan years

One of the early pupils of the postgraduate course became a force to be reckoned with. Mary Coonahan entered the program on December 1, 1895 and after completing it, was promoted to head of the aural house’s operating rooms and clinics. She became Assistant Superintendent of Nurses, then Matron and Superintendent of Nurses in 1897, staying until 1923. During her tenure, Coonahan supervised scores of nurses. She carefully documented the details of each of her employees’ working habits and personal character in ledger books. If a nurse was deemed to be lazy or insolent, it was documented in the ledgers. If she was kind and gentle with the patients, that was noted as well.

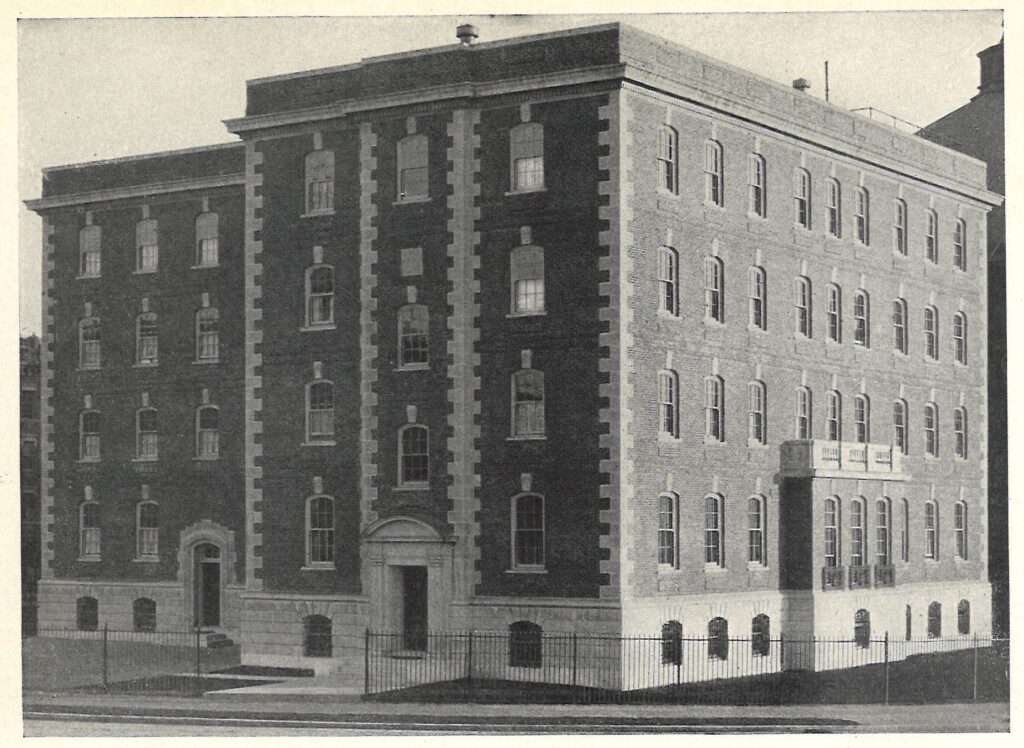

The ledgers form a picture of life at the institution and of the time. Nursing staff lived as a community in The Nurses’ Home, which opened in 1909. This four-story brick building still stands in Charles Street Circle, at the southwest corner of Charles and Cambridge Streets as a boutique hotel. The building was home to 100 nurses and domestic servants, who were frequently paired two to a room. Rooms were sparsely furnished with a bed, a three-drawer dresser with a mirror, a wall desk with a wooden chair and a rocking chair. Bathroom facilities were shared. There was a common room used as a living room for group activities such as card games and dance instruction. Nurses had long days, heavy workloads, and low pay. In 1915, the average annual salary was $287.00 per year (equivalent to less than $9,000 per year today). However, career options for women were limited in the early 20th century, which made a job at the hospital one of few respectable ways for young women to earn a living.

Coonahan was more than a strict disciplinarian: she was an advocate for education for women. She lobbied successfully to have her students exempt from cleaning and housework on the wards so they could focus on their education. She created a 60-day elective for nurses at MGH to study eye and ear nursing. Her mission was to create a proficient workforce of specially-trained nurses who could provide care to the unique patients of Mass Eye and Ear.

After she left, Coonahan was remembered for her great impact on the institution and to the field in general. The hospital’s 1923 annual report discusses the impact she had during her 26 years at the helm. “No other woman in the country has as much knowledge of the nursing care of patients suffering with diseases of the Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat as Miss Coonahan has acquired during her connection with this hospital,” wrote Sally Johnson, RN, the newly-minted Superintendent. “Not only does she possess this knowledge but she has the power of imparting it to others.… [N]one will probably ever possess the qualifications which she has for teaching at the Infirmary.”

Following Coonahan and leading the next several generations of nurses trained in the specialized care for eye, ear, nose, and throat patients at Mass Eye and Ear were long-tenured leaders in the field. Johnson served as Superintendent for 23 years while her successor, Dorothy Tarbox, RN, celebrated more than 30 years of nursing at Mass Eye and Ear with the last nine spent as superintendent. The combined leadership tenures of these three women spanned 1897 to 1955. Notably, adding to the day-to-day challenges of nursing were the second immigration wave in Boston (1880-1920), the 1918 influenza pandemic, World War I, the Great Depression, World War II, the beginning of the baby boom, and the Korean War.

At the forefront of nursing education

The tradition of Mass Eye and Ear as an incubator for nursing training and education continued through the 20th century. Abby Helen Denison, RN was a 1924 graduate of the MGH School of Nursing and an instructor at Mass Eye and Ear for four years. In 1927, The American Journal of Nursing published Denison’s mixed critique of the Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Manual for Nurses by Roy H. Parkinson, MD. She wrote: “In general, however, the chief criticism is that it is not primarily a nursing book…It is chiefly lacking in nursing procedure and it seems also that more time should have been given to eye work, as a whole.”

Perhaps this was the catalyst needed for a more nurse-centered textbook. In 1929, The Macmillan Company published Denison’s A Textbook of Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat Nursing, which was the first textbook written by a member of the Mass Eye and Ear Nursing School and—as noted by Charles Snyder in his book Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Studies on its History—likely the first textbook on the subject written by a woman who was a nurse. After Denison’s first edition, two additional nursing instructors, Lyyli Eklund, RN and Maria Scherer, RN were responsible for eight new editions or reprints that were published until 1943.

Another graduate of that 1924 class, Mary Estelle Shepard, RN, BS in Ed., MA wrote Nursing Care of Patients with Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Disorders in 1958. Shepard was a teacher and a nurse by training. She attended the Salem Normal School and taught in the Franconia, New Hampshire public schools before attending nursing school at MGH. She then taught at the Framingham Union Hospital School of Nursing and at Mass Eye and Ear. Also a graduate of Boston University and Teachers College, Columbia University, she was superintendent of nursing at Mount Auburn Hospital for 20 years.

Specialty training in the care of eye, ear, nose and throat patients provided by Mass Eye and Ear was highly regarded. The 1939 annual report notes that in addition to local hospitals sending nurses to the Infirmary for professional development, institutions in other states followed suit. Among them were industrial nurses from the Central Railway Company in Atlanta, Georgia; a group from a hospital in Philadelphia; nurses from Winnipeg, Ontario; and from the Mayo Group in Rochester, Minnesota.

The staff of New York St. Luke’s Building for Care of Contagious Diseases also sought expertise in the care of patients with infectious diseases as Mass Eye and Ear had been extending care for decades in the Gardner Building, which was specifically designed for patients requiring this level of treatment.

Nursing today

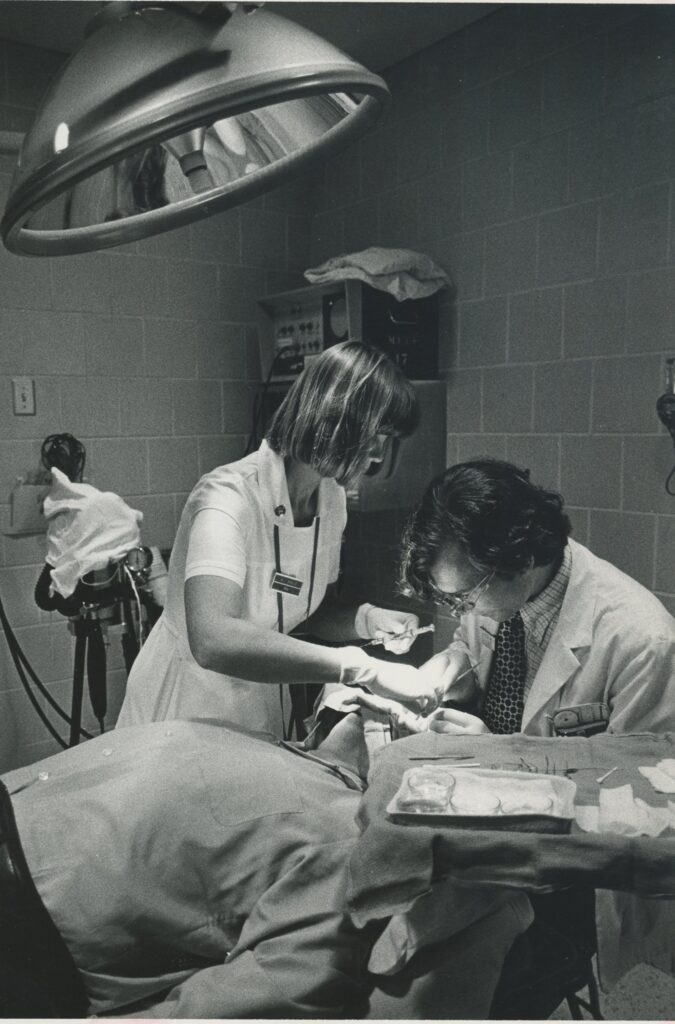

Nursing training at Mass Eye and Ear has evolved a lot through the years, but the commitment to the highest standards of practice and patient care has remained the same. Nurses come to the hospital to join programs that support skill acquisition and continued learning. One such program is the Nurse Residency, also known as Transition-to-Practice, which encompasses organizational orientation, practice-based experience on the units with preceptors, and supplemental learning activities to promote professional development. The goal of the program is to allow nurses to build on their skills and integrate them into their new role as a licensed nurse.

Mass Eye and Ear also has a robust Clinical Recognition Program, a pathway for clinical advancement that encourages nurses in direct patient care positions to develop professionally. Completion of the program involves working with a coach to develop a portfolio demonstrating clinical practice, professional growth, and ability to work collaboratively with others.

Certification is another way in which today’s nurses develop their practice and gain mastery of skills. Mass Eye and Ear currently has 30 certified nurses with demonstrated expertise in professional development, infection control, perioperative practice, ambulatory perianesthesia, otorhinolaryngology, pediatric, critical care, and emergency nursing.

The commitment and dedication of Mass Eye and Ear’s nursing team is as alive today as it was 200 years ago. The longevity of senior staff contributes to the continuity of care that patients depend on. The seven directors on the nursing leadership team have a combined experience of 175 years. So this 200th May and every day, we appreciate and acknowledge all of our nurses past and present for their professionalism, hard work, and dedication to MEE and its patients.