Mass Eye and Ear is celebrating its 200th anniversary, and the Focus blog each month will have stories on the hospital’s past, present and future. In this first post, the team at the Howe Library at Mass Eye and Ear details the founding of Mass Eye and Ear and how its mission has carried on from its first patients in 1824 through today.

In 1850, at the dedication of the first building intentionally constructed to house what was known at the time as the Massachusetts Charitable Eye and Ear Infirmary, its founder Edward Reynolds, MD offered some sound advice: “There are periods in the history of every individual, and every institution, in which it is wise to pause for a moment, and examine the landmarks that designate its points of progress; that we may gather up a lesson of wisdom from the past, and be stimulated to new exertions for the future.”

The year 2024 marks the 200th anniversary since Massachusetts Eye and Ear first saw patients, and as Dr. Reynolds wisely noted, this is a good time to reflect on the past and imagine the possibilities for the future. Indeed, the slogan for the year-long anniversary celebration is “A Legacy of Healing, a Future of Hope.”

To appreciate how long ago 1824 was: John Quincy Adams was elected President, Beethoven premiered his Ninth Symphony in Vienna, and the Marquis de Lafayette, the last surviving major general of the Revolutionary War, was given a hero’s welcome on a tour of the then 24 states in the United States of America.

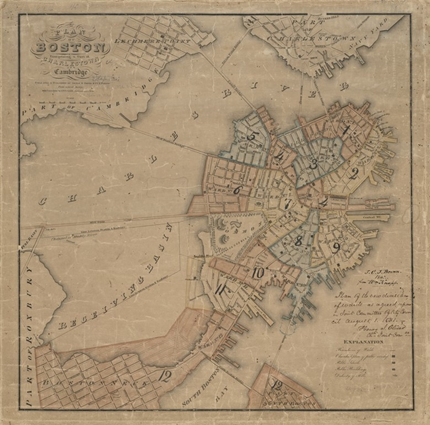

Boston itself had only been incorporated as a city two years prior, in 1822. The city then looked nothing like it does now, being little more than a swampy peninsula surrounded by mudflats.

Between 1820 and 1850, the population of Boston exploded from 43,000 citizens to 137,000, a more than 3-fold increase. The vast majority of this growth was due to European immigration. Many of those who came were laborers working for the booming regional textile, railroad and shipping industries and other trades, including carpenters, masons, blacksmiths and sailors. These workers were most likely to suffer occupation-related injuries; and, they were also the least likely to be able to afford medical care.

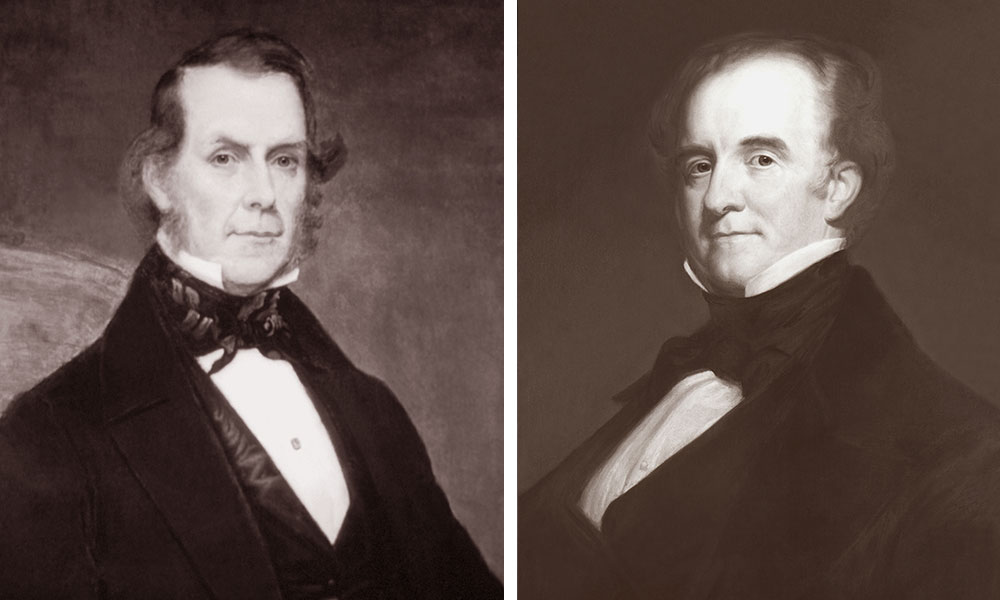

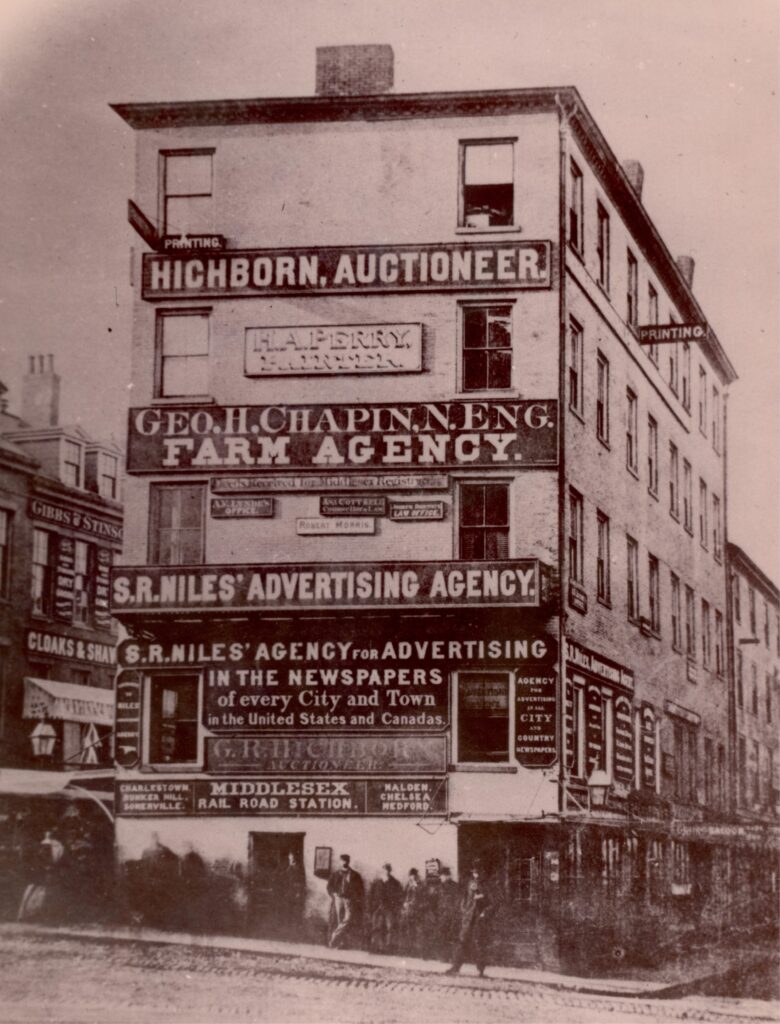

During this time, two young doctors, Dr. Reynolds and John Jeffries, MD, took it upon themselves to treat the eye diseases of the Boston poor at a free public clinic. While they were born into privilege, they were empathetic men with a strong sense of social justice. They recognized that if people could have early access to quality eye care, many diseases leading to blindness could be completely prevented. They rented one small room, one afternoon a week in the old Scollay Building in Scollay Square, and on October 1, 1824, the Boston Eye Infirmary was born.

It quickly became apparent that the need was great enough to expand the endeavor in terms of space, manpower and services. On December 29, 1825, Drs. Reynolds and Jeffries met with a group of Boston’s wealthy donors at the Exchange Coffee House, hoping to encourage them to support their dream of a new specialty hospital. In the 15 months since its founding, the Boston Eye Infirmary had treated 859 patients. Eighty-two of them were treated for ear diseases, indicating Reynolds and Jeffries were also willing to accept ear patients.

Each case had demonstrated to the two young doctors the importance of their clinic. Many patients afflicted with eye diseases could not work and if the disease became chronic, the person would most likely wind up in the taxpayer-supported public Almshouse. If the blind person was a head of household, his wife and children would of necessity go to the Almshouse with him. Yet most of these diseases, if treated early by an experienced eye doctor, could be cured. If the donors were to fund the Boston Eye Infirmary, the doctors argued, more worthy citizens could lead a productive life, and the Commonwealth would not have to support them and their families.

The two doctors had another goal to entice the donors: the new institution could become a teaching center. Physicians and medical students alike could learn about a wide range of eye diseases and hone diagnostic, treatment and surgical skills. The public would benefit when these well-trained practitioners became available.

The gentlemen gathered at the Exchange Coffee House were won over by Drs. Reynolds and Jeffries’ appeal, and voted unanimously “that, in the opinion of this meeting, a Public Institution…for curing diseases of the eye has become highly important, and will essentially serve the cause of humanity.”

They all got busy raising funds from additional individuals, and in 1827, the Governor of the Commonwealth approved an Act of Incorporation for the Massachusetts Charitable Eye and Ear Infirmary. The Infirmary moved out of the Scollay building to slightly larger rented quarters, now seeing patients Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays from noon to one o’clock.

As the population of Boston continued to grow, so too did the demands for the services of the Infirmary. From 1824 through 1836 Reynolds and Jeffries mainly saw outpatients in rented rooms. More serious cases were either treated at the patient’s home, with Reynolds and Jeffries doing house calls, or put up in local boarding houses at the Infirmary’s expense. It was clear that what had started in one room needed an entire building. The Infirmary purchased the Gore Mansion on Green Street in Bowdoin Square, fitted it with 20 patient beds and admitted its first patient on July 19, 1837.

That first inpatient, Richard Blood of Groton, Mass. was 41 years old, married with four children. In 1835, both his eyes were badly injured while blasting rocks. The damage to his eyes was so severe that he could no longer work, forcing him and his family to live at the Groton Almshouse. He was there for a year before he finally went to the Infirmary for help. After having been in the Almshouse for a year, he was so weak and malnourished that Reynolds and Jeffries did not attempt any procedures at first – they put him on a nutritious diet at a private lodging house for six weeks until he could regain his strength. The doctors then performed an initial surgery and sent him back to Groton. He returned again, and on July 19, 1837, he became the first inpatient. By November, Richard Blood’s sight had improved so much that he was able to support himself and his family, highlighting the crucial role this institution could play for the public

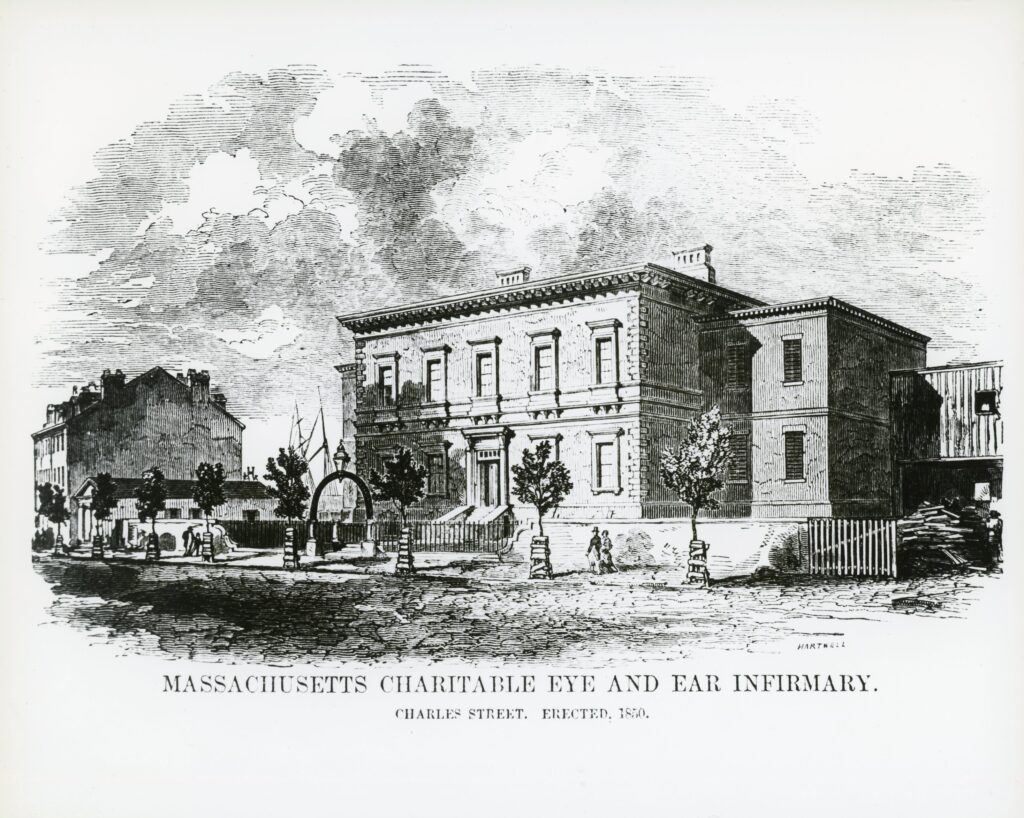

By the mid-1840’s the house on Green Street had outgrown demand: the number of patients had increased so much that some of them had to be housed in a barn. The Infirmary purchased land at 175 Charles Street, diagonally across the street from the current Charles Street/MGH MBTA station, and what is now the Whitney Hotel. There they built what was at the time a state-of-the-art hospital that could house 30 patients.

Throughout all this time, and indeed well into the 20th century, not a single physician received a salary for his work. The word “Charitable” in the name of the institution was not just a name, but a way of life for these doctors. They all had private practices and/or worked at one of the larger Boston hospitals but agreed to volunteer their time to help the Boston poor. On the wall of the main room of the Infirmary, the managers hung a sign: “This institution is designed for the benefit of the poor who are not able to procure relief elsewhere.”

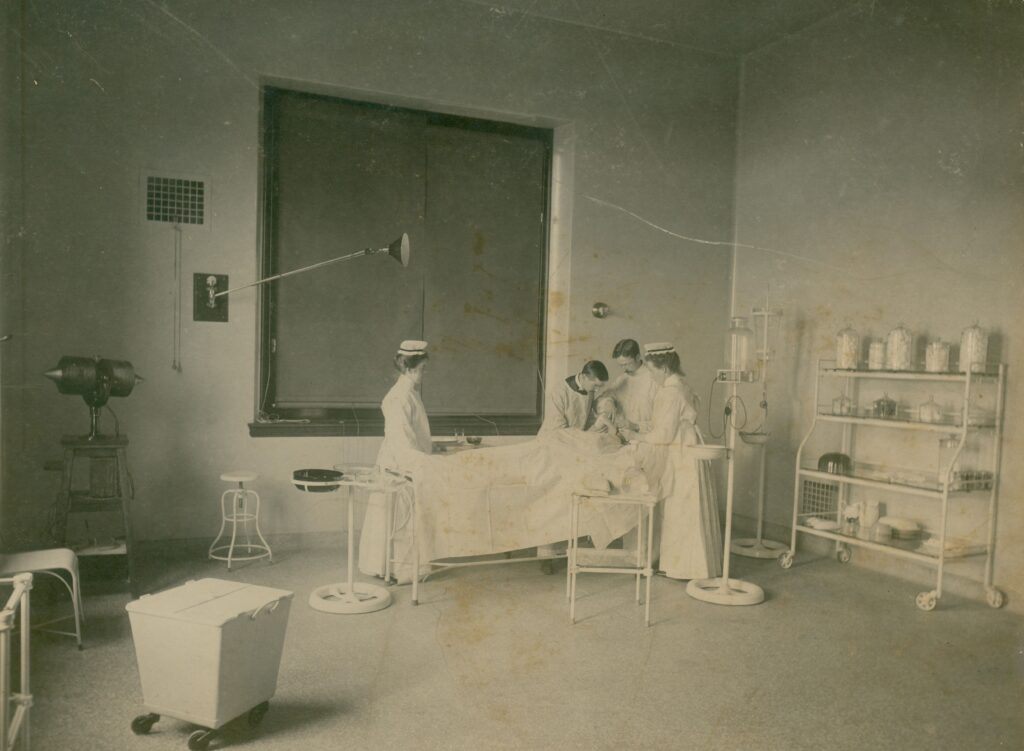

In1850, the Massachusetts Charitable Eye and Ear Infirmary opened its first dedicated hospital building. In just 26 short years, the Infirmary had seen more than 30,000 patients, establishing itself as a vital presence in Boston medical care. The hospital soon became a magnet for ophthalmologists and otolaryngologists who wanted to practice the highest quality medicine and surgery.

Mass Eye and Ear is today recognized as an international leader in clinical care, research and education. With all the innovations in medicine in the past 200 years, one thing has never changed: Mass Eye and Ear’s unwavering commitment to its patients.

If you would like to learn more about the fascinating history of Mass Eye and Ear, Charles Snyder’s book Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary: Studies on Its History is an excellent source.